After years of working in higher education, I’ve noticed that one crucial aspect of academia has gone largely unnoticed by the undergraduate population and more broadly, by the general public:

For reference, an entry level position in the United States pays $8.75/hour on average. Working 40 hours for 16 weeks (the typical length of a university semester) earns the employee $5,600. Adjuncts with advanced degrees, often PhDs which takes upwards of 8-10 years to complete, can earn as low as $1000 per 16-week course. This means that a full adjunct teaching load of three courses (at a single university) can pay less than minimum wage for entry level positions.

At the time of this write up, over 75% of faculty positions are filled by part-time faculty such as adjuncts. This is true not only at large state universities, but also at local community colleges, private 4-year colleagues, and yes, even ivy league universities. This issue is rampant throughout the United States, and possibly around the world (I have not researched this topic extensively outside the US).

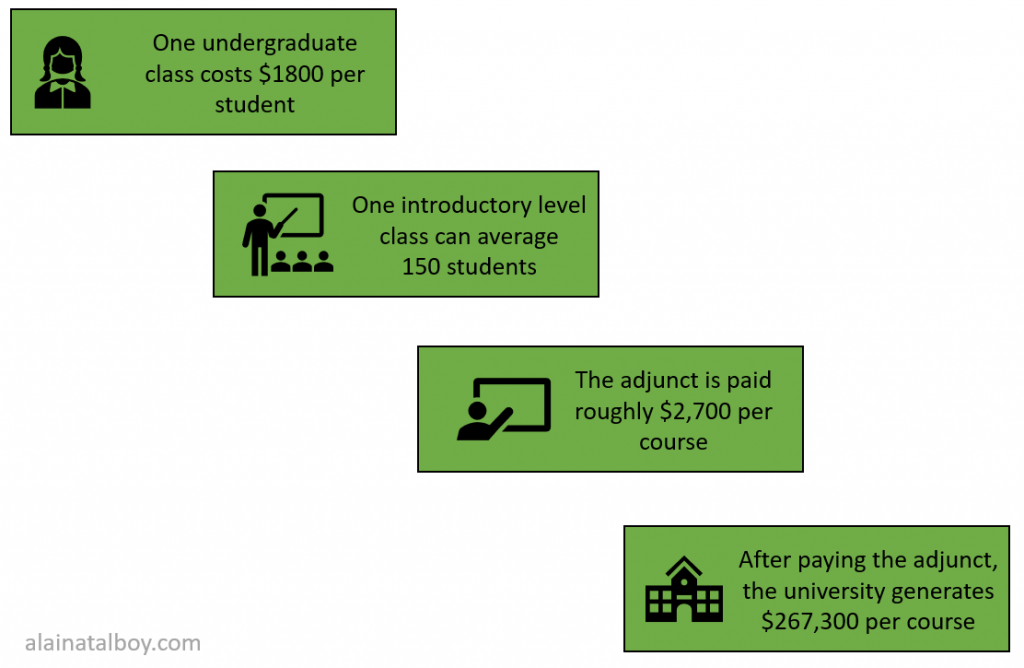

The average university student pays $594 per credit hour. With most college courses being at least 3 credit hours, the cost per class is typically around $1800 (rounding up for simplicity). This $1800 is just the cost per class (not including course materials, living arrangements, food, etc.).

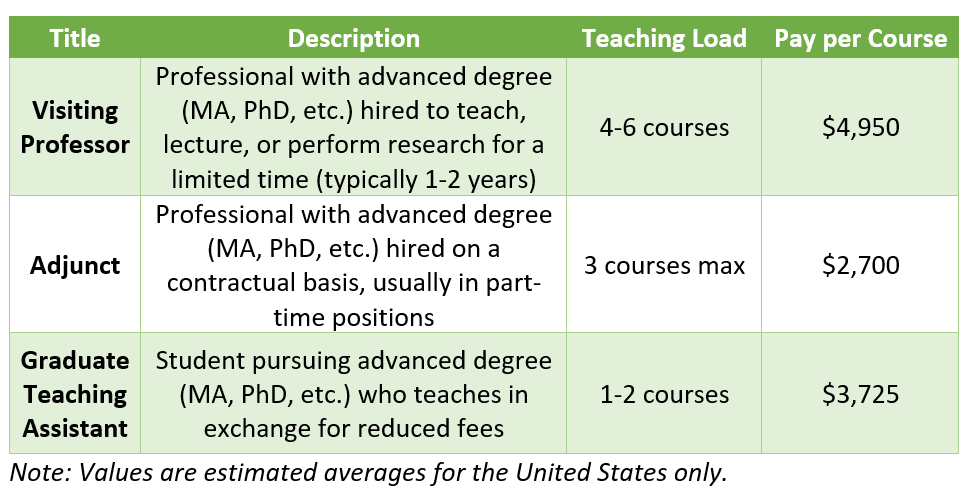

Now let’s turn to the person who is actually teaching the course. This person could be a tenured or tenure-track professor, a visiting professor, an adjunct, or a graduate student. For the purposes of this article, though, I’m not going to expand on a tenured professor since that topic has been discussed at length elsewhere. Instead, I want to focus specifically on the type of faculty most commonly employed by universities: adjuncts.

In higher education, over 75% of the faculty positions do not have and will never lead to tenure. This means that over 75% of those teaching in higher education are on fixed-term contracts like visiting professors, adjuncts that are hired for a single course, and graduate students who are teaching in exchange for their graduate training. Of those positions, 50% are adjuncts. As an undergraduate student, that means that you have likely encountered numerous professors who were teaching your course for the abysmally small rate shown in the chart.

Adjuncts are not allowed to teach more than 3 courses at a single university because that keeps them in a “part time” role. Some articles have tried to highlight the positives of being in such a tenuous position, but in reality the downsides far outweigh the positives for most adjuncts. The university does not provide adjuncts benefits afforded to their tenure-track peers such as health insurance, retirement funding, or even technology and office space to meet with students. Instead, these “part time” educators have to make due with shared resources that are subpar and hope they can afford to cover any unexpected health problems out of pocket. In one extreme case, a university failed to pay its adjunct staff due to budget issues, and yet expected adjuncts to continue teaching.

Many have called the adjunct vs tenure-track debate a system built on slavery. However, I would disagree. Instead, I refer to academia as a tiered system, one level for those few of privilege and unending university support through tenure. The other given scraps, with little care or regard for their personal well-being. In some rather horrifying cases, such as Thea Hunter, the not-so-hidden pyramid scheme of academia becomes very clear.

I’ve thrown a lot of numbers and information at you in a very brief write up, but let’s put them together to really see what kind of picture this paints.

One student pays an average of $1800 per course. An introductory course can average between 150-300 students, but for the purposes of this write up I’ll restrict that number to 150. An adjunct who is hired to teach one course is paid roughly $2,700 for that course.

This means that after paying the adjunct, the university generates a whopping total of $267,300 per class.

The typical bachelors degree requires 120 credit hours. That’s for a single student. This number becomes exponential as you start to think about the number of people starting college every year (19.9 million students in 2019).

And the university can generate upwards of a quarter million dollars from one introductory course.

That number is … staggering.

The not-so-hidden problem of higher education is that university courses are built on the backs of those who are highly educated but cannot find a permanent role. Why? Because the very universities they teach for eliminated job security by replacing tenured roles with highly precarious part-time positions. The tenure roles that are still available are highly competitive, often being filled by professors that already have a tenure track position at a different university. Therefore, few options outside of adjuncting exist for these professionals who want to stay in higher education.

This inappropriate (and what should be illegal) pay structure is one of the most glaring, disturbing, and leading failures of academia and higher education in general. The courses and education offered by universities are built from the materials, time, energy, and resources of adjuncts. Without them, there is no higher education. Adjuncts need as much as support as their tenure-track peers through fair compensation, financial packages to save for retirement, mentorship and personal growth, technical resources to advance teaching practices, and others. Without more concrete support, there is little incentive to stay in academia.

Based on the estimated values above (keeping in mind that these are estimates), universities can clearly afford to pay adjuncts a much higher salary while still achieving revenue goals to offer supplemental services to education. By leaning in to support adjuncts as much as they support tenure-track professors, institutes of higher learning can finally start the massive structural changes that will put their primary focus back on education. In doing so, future educators will have the tools and systems in place that allow them to focus on what truly matters: education.

Copyright © 2021, Astute Science LLC All Rights Reserved