What I Wish I Knew: A Field Guide for Thriving in Graduate Studies

Reference Dependence in Bayesian Reasoning: Value Selection Bias, Congruence Effects, and Response Prompt Sensitivity

Ethics Violations in Human Research

Ethics Violations in Human Research throughout History

Ethics are commonly viewed as norms for conduct and how we determine right from wrong. In human research, these ethics are the guidelines under which we evaluate our work and how it affects people.

Ethics review boards are established to evaluate the ethics of a research protocol. While not comprehensive, below is a list of ethics violations that led to ethical guidelines such as those established in the Belmont Report.

Please note that reading through these examples will cause discomfort and unease.

-

- 1846: Gynecological procedures tested on enslaved women without anesthetic

-

- 1932: Start of the Tuskegee experiments withholding established syphilis treatments from black men

-

- 1939: Nuremberg atrocities committed during WWII

-

- 1939: Unit 731 illegal testing of chemical and biological weapons on civilians

-

- 1980s: Blood donated from the Nuu-chah-nulth tribe and the Havasupai tribe was used by multiple research institutions without informed consent of how extensively their DNA would be used

-

- 1990s: Costa Rica used as an unregulated pharmaceutical testing ground for infant and children treatments

- 2005: Private institutions are beneficiaries of amassing the world’s largest bank of indigenous blood and database of human origins and migration, all at the expense of indigenous peoples

-

- 2015: Ethnographer refuses to provide crucial information in search for murderer and potentially engaged in illegal activities under the guise of “research”

I update this list as I receive additional examples. If you have an example to add to the list, please email me a link to the violation with a brief, one or two sentence summary.

Support of Friends and Family During Grad School

Building a Support System to Survive Graduate Studies

Starting graduate studies can feel like a very lonely choose-your-own-adventure story. It’s a story that you can’t really explain or articulate the details of until you’ve reached the very end to look back at the place you started. It’s exciting! It’s new! And it can be overwhelming without a support system in place.

The twists and turns on your road, what you’re experiencing and the responsibilities heaped upon you, will not be the same as others who go straight into the workforce after completing a bachelors degree. It won’t even be the same for colleagues also working on an advanced degree. The paths we take as scholars, researchers, and experts are individualised and unique, which can make us feel incredibly alone.

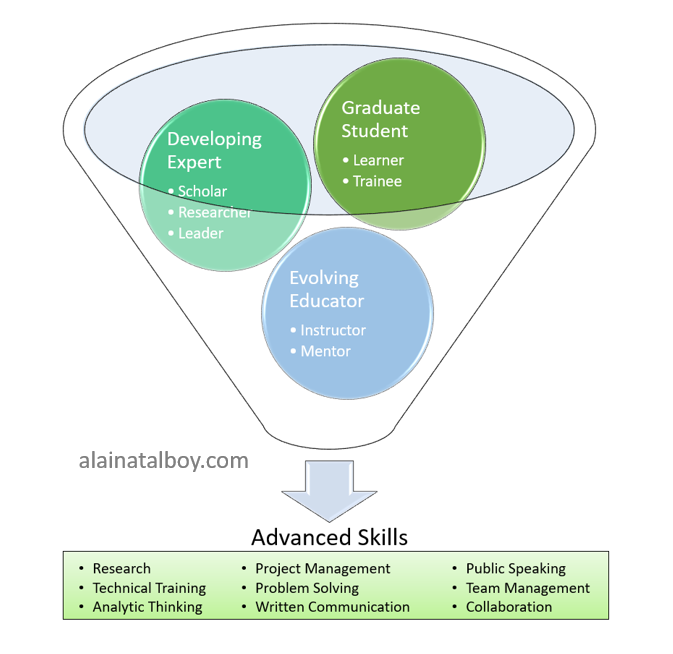

Our brains convince us (quite easily, sometimes) that no one will truly understand how hard, challenging, and just how draining all of the responsibilities are when you stop and really consider the balancing act that is required for earning an advanced degree. A graduate student is not only a student. During grad school, we are also building a teaching portfolio, possibly teaching for the first time! Same with research, writing, mentoring, all on top of developing a budding expertise; with the title of “student” coming through first and foremost.

Support Sans Guidance

There will be times throughout your degree when you will feel so completely alone, stressed, and overwhelmed. These are the times when you need to have a solid support system in place. Talking to people who have never gone through graduate studies can be a challenge, not through any fault of their own though. They simply do not know what you are experiencing. To demonstrate, here are some of the typical questions and statements you will get from loved ones (apologies in advance for the anger these may induce!):

• When will you be done? Or when will you graduate?

• When will you get a real job?

• Are you going to be a forever student?

• It’s just school. It can’t really be that hard.

• When are you going to grow up?

• Send your resume to that university down the road to get a job. You don’t need to wait for an “application cycle.” [Alternatively: What is an application cycle?]

Trust me, you will encounter these questions and more, and you may internally rage every single time. Or sigh. Or cry. You know, depending on where you are in your own path. You might notice that many of these questions spawn directly from the idea that you are just a student even though you are so much more. I know in the moment it can be hard to remember, but take a breath. These are likely the same people who supported you throughout your undergrad degree. They are coming from a place of love and caring but simply don’t know or understand what it is you are going through.

Keep in mind that most people will not want or try to get an advanced degree, and therefore they have no concept of what is actually involved in graduate studies. They probably have no idea what comprehensive exams are, let alone know or care that there is a difference between a master’s thesis and a doctoral dissertation (or the reverse in the UK, for example). We academics know that these are completely different things, but to others it’s irrelevant. What your chosen friends and family really care about is you, how you are doing, and whether you are happy in the choices that you make. They want to support you, but you have to help them understand how to do that.

Another Task, Albeit an Important Task

I would argue that it is fairly impossible to make it through an advanced degree without developing some kind of support system. You’ll be stressed. You’ll be sad sometimes, and put through the ringer other times. You are going to need the support of your chosen friends and family throughout your degree path, regardless of whether they’ve been through it or not.

Without experience or guidance, people will ask those questions listed above with the best intentions at heart, thinking it’s probably an easy question to answer. Your task is to help your support system become better supports and allies throughout your degree by having an answer ready to each of those questions. More importantly, you will need to (gently) correct misconceptions that graduate studies are just like undergrad but harder.

Showing your friends and family how to be a good supporter will help them help you. Explain that getting an advanced degree is worlds beyond just “more school” but is in fact the first job at the start of your career (even though it comes with little to no financial support). Demonstrate how you are laying the groundwork to become an expert in your field, and that it takes time, energy, strength of will, and so much more. Teach them that you are becoming an educator, a researcher, a scholar, and all of these things take a tremendous toll on our brains and bodies. Help them understand how to support you in the ways that you need to be supported.

Talking to your friends and family, practicing how to explain complicated topics such as “what does a graduate student really do?” will help them understand and appreciate the challenges you are facing. Talking through these topics will also help you become more centered and grounded in the steps you are taking in your career. The particular skill of translating from jargon to everyday language will also become valuable the further you go in your career, no matter whether you stay in academia or leave for the larger fields of industry, government, non-profit, and private sectors. Articulating complicated material in easy ways to understand is a skillset that opens many career doors.

Figuring Things Out

Sadly, here I where I tell you that external wisdom will only help to a point in this part of the choose-your-own-adventure. Everyone is unique and the support each individual will need is dependent on who they are as a person. What worked for supporting me throughout my studies is not going to be the same that works for you. Adding another layer of difficulty to this task is the fact that the support you need at the beginning of your graduate degree is not necessarily going to be what you need in the middle, nor towards the end. You have to be flexible enough to change and grow as you advance, and also willing to express changes needed in your support as time goes on.

Be patient. You may not know what is good or bad in terms of support until you get there. But you’ll figure it out! After all, you’re on your way to becoming an expert in your field. You got this.

If you need help figuring out the answer to some of these questions, grab some time from my calendar and we’ll discuss it over a cup of coffee.

Shout out to my amazing lab mates and podmates for being a constant source of inspiration, joy, and adventure throughout our time in grad school.

Personal Reflections as a Woman in STEM

Personal Reflections: International Women's Day 2021

Disclaimer: The point of view that is presented in this post may not be representative and is provided as an example of how some women are treated in traditionally male-dominated fields. The point of view I represent is my own as a white cis female scientist. Yes, the qualifiers are necessary. The experience I have may be vastly different from a BIPOC cis female scientist versus a white trans male, etc. As a white woman, I recognize there is a level of privilege I experience that others may not. Likewise, I experience stigma, sexism, and systematic issues specifically because I am a woman in STEM. The lens I bring to this conversation reflects my personal experience and may not be consistent with others’ experiences in similar situations.

As many of my colleagues and friends can attest, I absolutely adore all things math and statistics. I love numbers! I love using the scientific method to uncover how people interpret numeric information in order to make informed decisions. I love learning about how people perceive math and statistics. Even more, I love changing opinions about statistics and how useful numbers are in everyday life!

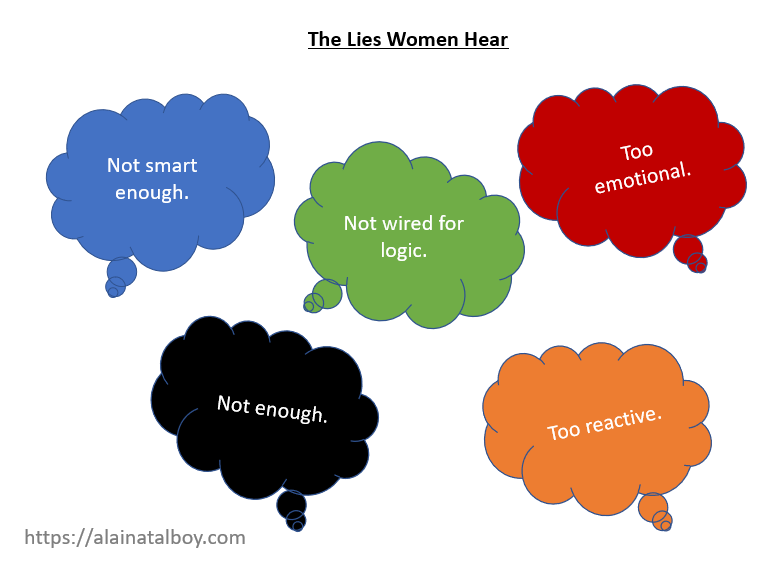

Historically, math, statistics, and most science majors at universities were reserved for men because people wrongly believed that women could not handle the logic and reasoning required to advance. (Note: that research was published in 2014!) Despite the incredible work that’s been done to show equal aptitude and success regardless of gender, I’ve personally encountered this belief throughout my career more often than I care to admit.

One particular example comes to mind, from when I was much younger than I am now. I was only a few years out of high school, enrolled in Calculus III at my local community college. I was majoring in mathematics and physics at the time, actively participated on the Math Olympics team, and worked full time to support myself.

The professor I had for my entire calculus series did not like me and made no secret of it. On several occasions during the long evening lectures, I would ask for clarification on how to solve a problem. He would respond by dismissing the entire class for the evening instead of showing us the solution. At the end of the semester, that same professor pulled me aside to say even if I passed the final exam, he would still fail me because I do not belong in STEM. So instead of showing up for the final, I gave up. I dropped out of college entirely and went to work full time in a completely different city.

It took many years to recover from that exposure to male gatekeeping in STEM, and my self-esteem was shattered. I thought maybe he was right; I would never be a scientist. I wasn’t cut out for the really challenging mental work of being a researcher. I would never succeed in a career that required advanced mathematics even though it is a topic I love so much. I internalized so many of the stereotypical statements women hear when they want to pursue a future in these fields.

Fast forward to 2019, after a lot of self-reflection and the support of an amazing group of friends, colleagues, and mentors: I earned my PhD from an R1 university under the guidance of the most awe-inspiring woman I have ever met. I was part a lab full of amazing women who held zero regard for glass ceilings and relentlessly pushed forward despite many obstacles. These women are my inspiration, and I continue looking up to them every day.

I am now a full-fledged scientist with expertise in numerical reasoning and decision making. I get to do research and make new discoveries about the brain and human cognition. How cool is that?! Experimental design and advanced statistics are my bread and butter for exploring the human brain and why we behave in the ways we do. I publish routinely on reasoning, transitioning to industry, and continue to mentor future scientists through my Friday afternoon coffee chats. I work for a company that values research and hires people from all walks of life. I get to do what I love every single day, what that professor told me I would never be able to do: research, educate, and continue learning.

My story could have gone a very different direction, and for awhile it did. I could have continued listening to the voice of others saying that women do not belong in STEM, let alone any field requiring advanced mathematics. I could have continued internalizing the beliefs that women are not capable of the same logic and rigor needed to advance scientific theory. I could have been one of any number of women with similar experiences who listened to those voices instead of their own.

But that’s not me.

My website is titled “Dare to Challenge the World” because I want to live this ideal every single day, while helping others do the same. Women belong. Full stop. No qualifiers. These outdated lies about what women can and cannot do, and who is intelligent enough or logical enough to be a scientist, are antiquated and have no place in the modern world.

On this International Women’s Day, I call on you to support and praise the women around you. Help them succeed on the path they wish to follow.

And if they have a PhD or any type of doctorate, call them Doctor. They earned it.

Happy International Women's Day 2021

Once an Academic, Always an Academic

Once an Academic, Always an Academic

I used to believe the term academic was reserved for graduate students and professors, and that going into industry would mean giving up that identity. Now I know better.

The transition to industry is difficult, and we need to talk about the practical challenges, emotional costs, and mental effort needed to make the jump. It is easy to forget that academia is just one field, and a rather small one at that. There are many other sectors out there to explore! I’ve seen people with advanced degrees get positions in medicine, technology (like myself), government, and nonprofit. There shouldn’t be a taboo about leaving academia when the majority of graduates are advancing on to positions with great pay and benefits.

Since many of us with a PhD are expected to become professors, there is little guidance for making the jump to industry. We are taught how to write curriculum vitaes, not resumes, and the nuances to portfolio presentations in industry are vastly different from those in higher education. I wrote a bit about these issues in Five ways your academic research skills transfer to industry.

The hardest part for me personally was the mental and emotional toll of losing my academic identity. We all know the saying that once you leave academia, you can’t go back. We wrongly believe that whatever reason causes us to leave academia is the same as willfully choosing to give up a part of our identity. At least, that is how it feels after spending literal years being trained for one and only one job.

I am hopeful that this conversation comes up during your first year in graduate school, so you can minimize a bit of the emotional and mental toll that it takes to leave academia. Because let’s face reality here: most of us will not get a tenure track position. And that is okay! In fact, for most of us that is better than okay! Yes, it might feel depressing to recognize that reality. You might be incredibly sad. You may feel heartbroken because it’s the only job you’ve known and/or wanted for the last few years. I acknowledge and respect those feelings. But I also know you will go on to do something else because in the end, being a professor is just a job. And there are so many jobs in the world that PhDs are capable of doing.

When I first left academia, I felt that too. I spent weeks agonizing over my choice. I subjected my partner to a 20-hour long drive (round trip) while I worked through all of those feelings and all of those anxieties. It felt like I was leaving a part of me behind because I gave up tenure track to go to industry. I didn’t know if I could continue publishing my own research. I didn’t know if I could still teach people things I found interesting. I was afraid of making the wrong choice and closing a door on a career path that I had spent so many long years working toward and had finally achieved. I was terrified.

Then I started working in my first role outside of academia, in the technology sector. I joined a research team that was agile, meaning research moved at a very quick pace and cycled every few weeks. Several of my colleagues also came from an academic background and held advanced degrees, so they understood what I was going through. They were a great resource for learning the ropes and making the transition smoothly. Through that first opportunity and subsequent offers, I discovered that what I enjoyed most about academia was the freedom and autonomy to pursue research in ways that I saw fit, which I had in every role I’ve taken since finishing my PhD. And though I miss my particular niche of research and the courses I taught, I am finding so much more fulfillment in my day-to-day work than I originally expected, simply because it has that freedom and autonomy I value so much.

From my experience, it took about a year to really come to terms with the fact that I would likely never return to academia, at least in the very strictest sense. But something I also learned is that I am still very much an academic, despite closing that first door to staying in higher education. I can still change people’s worldviews and make a difference. I can still be an educator and teach people things they didn’t know. I can still be a researcher and scholar and all of those things that come together to make me an academic. The only difference is instead of being called professor, I took on the title of user researcher, design researcher, behavioral scientist, or research scientist as my job dictates. I will always be an academic no matter where I go.

Addendum: My experience is with the US higher education system. Experiences in academic systems outside the US may be different.

Workback Plans: Planning for Success in Graduate School

Workback Plans: Planning for Success in Graduate School

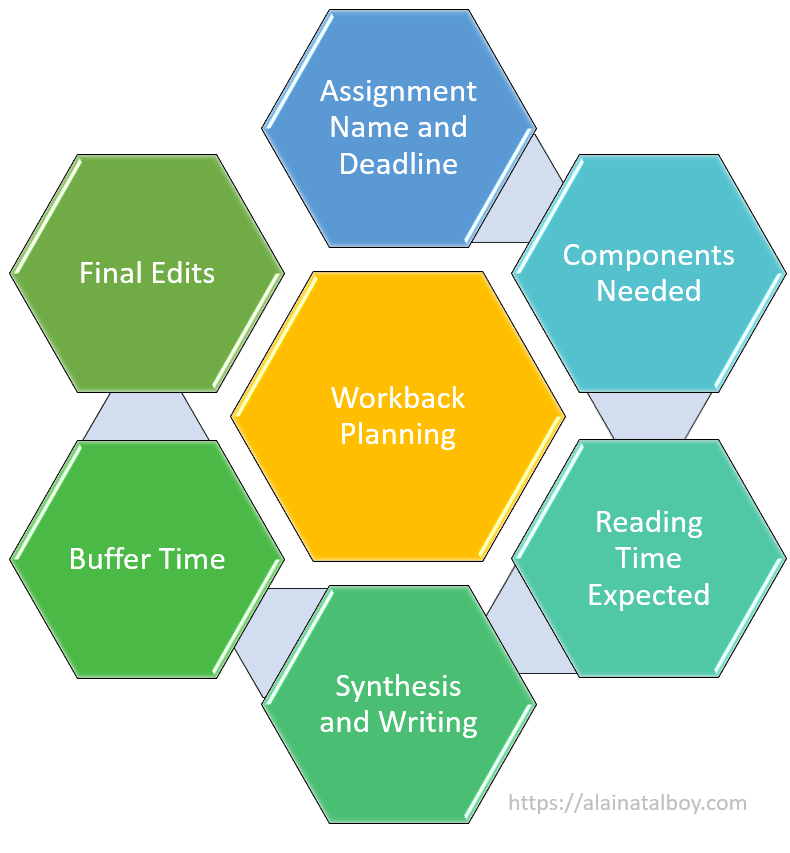

If you are considering an advanced degree or want to know how to make the most of your time each semester (without missing important due dates!), knowing how to design and implement a workback plan will be a tremendous advantage for you. The purpose of a work-back plan is to figure out where it is you want to end up at the end of the road, and then work your way backwards towards the beginning of the project establishing key milestones along the way.

A project plan may have different names depending on the industry you go into after graduation. Some call it project planning, workback plans, or some combination of the key words work, project, and plan. If you have never heard these terms before, that’s ok! This is a great time to learn about them and how to use them to your advantage throughout graduate studies and well into your career.

What is a workback plan?

A workback plan starts with the due date, the deliverable, and all the components that are needed to create the deliverable. For the graduate student (or even the studious undergraduate), practice creating, implementing, and closing out these plans starts with reading through a course syllabus at the beginning of the semester. [Cue the audible groans.] Yes, you must read the syllabus. Please read the syllabus. Over 90% of the time, this document includes literally everything you need to pass the class.

The course syllabus is a living document that includes a bunch of technical information (often required by the department/college/university), but many will include what is called a scheduled list of assignments. This list will provide all of the required chapter readings, assignments, quizzes, and exams dates. By reading through this document, the student will know what is expected of them throughout the entire semester for the course. As a student, a syllabus is an excellent guide that you can use to create your very own workback plan designed to help you succeed (i.e., pass the class).

Before we get into the nuts and bolts of what a workback plan includes, let’s take a quick detour to talk about software. Creating a workback plan doesn’t require fancy project management software, though if you do go that route there are several options available. I never personally used any of them so I cannot vouch for one over another. Digital alternatives include Excel, OneNote, and even an online calendar. However, no matter what method you choose, the only way a workback plan is going to actually help is if you put in the time and energy at the beginning of the semester and really think through what each course you are enrolled in is going to need.

A word of caution: The method you start with may not be the one that works the best for you, and some experimenting might need to happen. For example, I’ve tried using calendars, MS Project, OneNote, and Excel. For me, though, a pen-and-paper planner that spans the entire semester is a tried-and-true method that just works well. I use a combination of workback plans I’ve adapted over the years, to-do lists, and the everything journal method. Keep trying until you find one that fits you well and is adaptive enough to meet your personal needs. It doesn’t need to be perfect; it just needs to be good enough to get the job done. In the end, you’re looking for something that spans the entire semester, has enough room to write objectives for each class on each weekday, and can be easily referenced throughout the week.

Creating a Workback Plan to Succeed in a Graduate Course

Once you settle on which format you want to adopt, knowing that you may go through one or two formats before settling on one that fits you, it’s time to start laying out all of the pieces needed for your workback plan. In the case of a graduate class, you’ll need your course syllabus to plan time for required readings, assignments, quizzes, and exams.

The quizzes and exams are fairly straightforward. You just need to add them to the correct calendar date. Exams may need a “reminder” note a few days prior, just so you can quickly glance back through the material that will be covered.

Chapter Readings

Class readings are a little trickier, but start by placing them at the beginning of the week prior to the day the chapter will be covered in class. For most people, the beginning of a week will be Monday, and we plan the chapter reading for the week prior because you want to attend class prepared with questions about the material. The tricky part of chapter readings is that you can’t just sit down to read the entire chapter in one go and expect to learn all of that material. Instead, chapters need to be broken into reading “chunks” so you can process the material little-by-little over the course of a week.

Let’s say in one class, you are assigned two 30-page chapters assigned each week. That may seem like a ton of reading materials, but let’s break that down into smaller pieces. In total, there are 60 pages that need to be covered over the course of 5 days. Some of the material will be covered in class, but again you’re expected to read the material prior to attending class. If you break 60 pages over the course of 5 days, you should expect to read about 12 pages per day. This will vary slightly as you find natural reading chunks, but to start out with try planning for an even split across days.

On average, a person can expect to spend about 10-15 minutes reading 12 pages. But I want to call out that reading to learn is not the same as reading for enjoyment. Reading to learn also includes taking notes, filling in a chapter outline, answering the quiz questions throughout the pages, looking up definitions, etc. As a graduate student, you are building a body of knowledge that you can draw from throughout your career. Having organized notes that can be easily referenced again and again in the future will help you create that solid foundation of knowledge. (A companion article about building this knowledge base is currently in the works. Check back soon!) Therefore, consider allotting yourself 20 minutes per 12 pages just to make sure you are planning in time for that note taking.

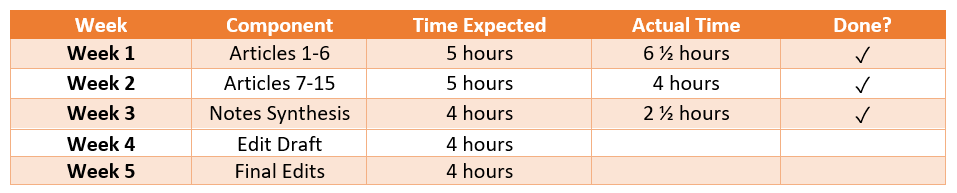

Here is an example planner snippet that shows how to break up each chapter reading. As you can see, the planner is split into five days for Course A.

The table includes the assignment section, how much time is expected, the actual time spent on that section, and a column to check it off when complete (because who doesn’t love checking off boxes?). This Done column will be really beneficial on days you feel like you didn’t accomplished anything because you can look back through your planner and see literally everything you’ve planned out and accomplished.

If you are a typical graduate student, you are likely enrolled in 3-4 courses per semester, which will require roughly 2 chapters of reading per week each. Following this method, you will spend about two hours per day reading course materials and taking notes.

Writing Assignments

Writing assignments take a lot more planning that chapter readings and quizzes. For undergraduates, class time will be spent covering the basics of what is required in the assignment, the writing style required (typically APA or MLA), and all of the core components that are needed to earn a passing grade. For the graduate student, these basics may or may not be covered in class. You may receive a PDF with instructions and possibly a grading rubric, but ultimately the assignment is up to you to manage.

Graduate students are expected to operate with more independence than undergraduates. This is when workback planning become an invaluable tool because these plans enable steady completion of small chunks of work that culminate in a major paper or assignment. As an aside, if there is any way to use your course materials to advance your personal research or scholarly interests, do it! Double dipping in this regard is a fantastic use of time!

An example writing assignment may be a research synthesis and analysis, covering at least 10-12 scholarly or peer-reviewed articles, with sections of what was learned as well as identifying the gaps left. This means you will need to plan time to:

-

-

- read at least 12 articles (plus a few extra because you never know if the articles you pick will actually end up being the ones you use),

- think through how they all fit together,

- write the synthesis,

- and finally edit,

- then edit again.

-

Knowing how much time it takes you to read a chapter is really useful at point because you can use that estimation to figure out how long the reading portion of this assignment will take. During this time, you will also be taking notes and making mental connections among the materials you’ve already read. This will help tremendously when it comes time to actually write your report. Writing the report will always take twice as long as you expect because it involves combining all of those notes you took, along with your own interpretation of the materials. Let’s use this current article that you’re reading as an example.

I wanted to write a piece about workback plans and how they help graduate students accomplish a lot in a little bit of time. I sat down one morning and started writing this piece based on everything I’ve read about project management, my own experience, and all the tips I’ve picked up along the way. It took about 2 hours to get the bulk of my thoughts down on paper. The next day, I read some more articles about project planning, graduate studies, and reread everything I wrote. At this point you may expect me to make some changes, but instead I make an effort to NOT edit anything for at least a day. I want to take in my work without rewriting or rethinking individual sentences so I walk away with the gist of my paper instead of the annoying details (like mismatched tenses or missing transitions).

The next day, I spent a few hours editing and reworking a few sections. A few days later, because you absolutely need to put it down and walk away for a few days, I came back with fresh eyes and read the report one more time. This resulted in one last round of edits before scheduling to post.

In total, the writing process for this particular article took me roughly a week. However, I drew on a knowledge base that I built over the course of 10+ years, with both research and personal experience to back it. In graduate school, a piece this long would have taken me 4-5 weeks (or more) to write and edit before submission. Knowing this, make sure you plan some “buffer time” so you don’t end up with your back to a deadline and only half your report written.

Planning A Semester::Planning a Career

Sitting down with your course syllabus at the beginning of the semester will help you create a workback plan to cover all of the course materials with hopefully a little time to spare. Once you’ve created each course plan, you can start weaving them together to create a master semester schedule for yourself that you can refer to each day to see everything you’ve accomplished, as well as provide the roadmap for where you want to get to at the end of the class.

I’m not saying this schedule will be perfect. There will absolutely be bumps and changes along the way. But putting in the time and effort at the beginning of the semester will help you navigate those bumps and changes more gracefully than if you didn’t have a plan.

As you start to incorporate these practices into your daily life, you’ll find that the time you spend in the lab may decrease. You don’t need to dedicate 80 hours per week to graduate school if you know how to manage your time well. Although work-life balance is another topic for another post, workback plans are one of the many tools you’ll pick up during graduate school that will help you create strong boundaries between your work and personal life. Getting good at estimating how long projects take will also benefit you long after you finish your degree and move on to the job market. Every company wants an employee who is productive, efficient, and requires little hand-holding. Getting good at creating, implementing, and closing out workback plans in graduate school can give you a leg up on the competition.

If you need help creating your first plan or modifying it after unexpected changes (in the project, materials, or just life in general), jump over to Coffee Chats to schedule some one-on-one time with me.

Adjuncts in Academia

The Not-So-Hidden Pyramid Scheme of Academia

After years of working in higher education, I’ve noticed that one crucial aspect of academia has gone largely unnoticed by the undergraduate population and more broadly, by the general public:

For reference, an entry level position in the United States pays $8.75/hour on average. Working 40 hours for 16 weeks (the typical length of a university semester) earns the employee $5,600. Adjuncts with advanced degrees, often PhDs which takes upwards of 8-10 years to complete, can earn as low as $1000 per 16-week course. This means that a full adjunct teaching load of three courses (at a single university) can pay less than minimum wage for entry level positions.

At the time of this write up, over 75% of faculty positions are filled by part-time faculty such as adjuncts. This is true not only at large state universities, but also at local community colleges, private 4-year colleagues, and yes, even ivy league universities. This issue is rampant throughout the United States, and possibly around the world (I have not researched this topic extensively outside the US).

What is the student cost and how much do universities pay the person who is teaching these courses?

The average university student pays $594 per credit hour. With most college courses being at least 3 credit hours, the cost per class is typically around $1800 (rounding up for simplicity). This $1800 is just the cost per class (not including course materials, living arrangements, food, etc.).

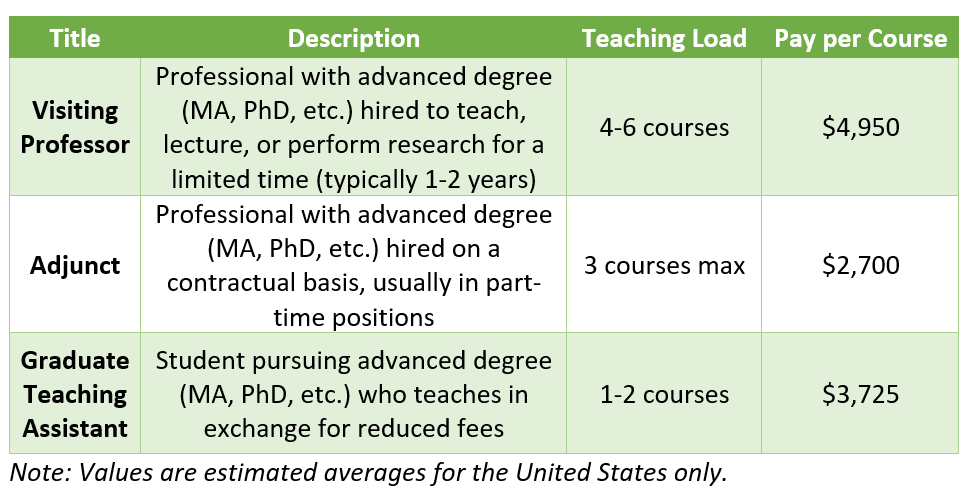

Now let’s turn to the person who is actually teaching the course. This person could be a tenured or tenure-track professor, a visiting professor, an adjunct, or a graduate student. For the purposes of this article, though, I’m not going to expand on a tenured professor since that topic has been discussed at length elsewhere. Instead, I want to focus specifically on the type of faculty most commonly employed by universities: adjuncts.

Why focus on adjuncts and part-time educators though?

In higher education, over 75% of the faculty positions do not have and will never lead to tenure. This means that over 75% of those teaching in higher education are on fixed-term contracts like visiting professors, adjuncts that are hired for a single course, and graduate students who are teaching in exchange for their graduate training. Of those positions, 50% are adjuncts. As an undergraduate student, that means that you have likely encountered numerous professors who were teaching your course for the abysmally small rate shown in the chart.

Adjuncts are not allowed to teach more than 3 courses at a single university because that keeps them in a “part time” role. Some articles have tried to highlight the positives of being in such a tenuous position, but in reality the downsides far outweigh the positives for most adjuncts. The university does not provide adjuncts benefits afforded to their tenure-track peers such as health insurance, retirement funding, or even technology and office space to meet with students. Instead, these “part time” educators have to make due with shared resources that are subpar and hope they can afford to cover any unexpected health problems out of pocket. In one extreme case, a university failed to pay its adjunct staff due to budget issues, and yet expected adjuncts to continue teaching.

Many have called the adjunct vs tenure-track debate a system built on slavery. However, I would disagree. Instead, I refer to academia as a tiered system, one level for those few of privilege and unending university support through tenure. The other given scraps, with little care or regard for their personal well-being. In some rather horrifying cases, such as Thea Hunter, the not-so-hidden pyramid scheme of academia becomes very clear.

This is a lot to take in. Do you have a tl;dr?

I’ve thrown a lot of numbers and information at you in a very brief write up, but let’s put them together to really see what kind of picture this paints.

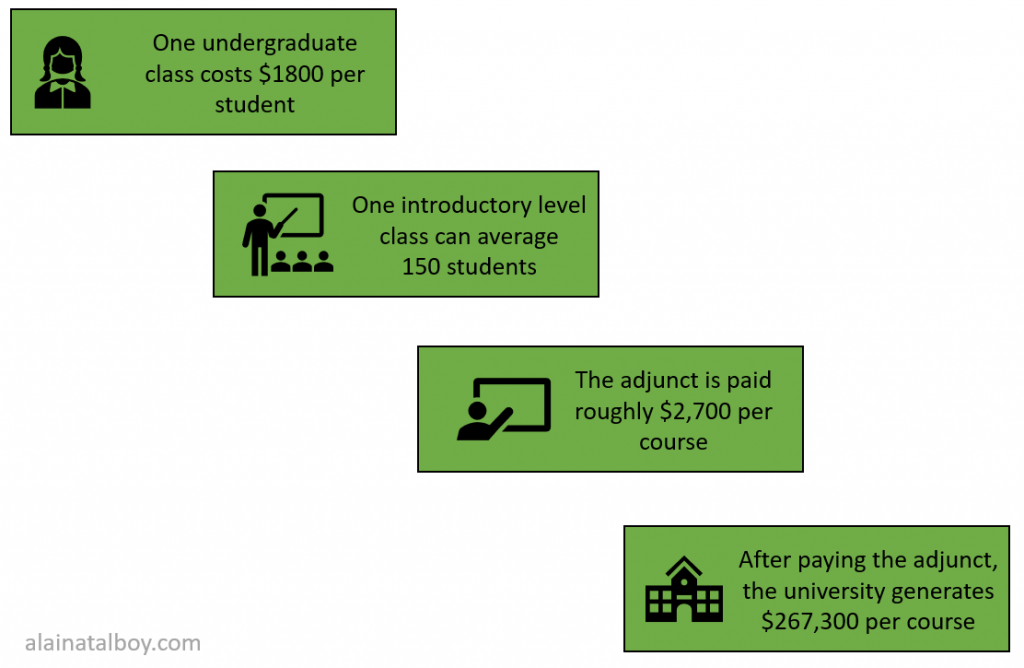

One student pays an average of $1800 per course. An introductory course can average between 150-300 students, but for the purposes of this write up I’ll restrict that number to 150. An adjunct who is hired to teach one course is paid roughly $2,700 for that course.

This means that after paying the adjunct, the university generates a whopping total of $267,300 per class.

The typical bachelors degree requires 120 credit hours. That’s for a single student. This number becomes exponential as you start to think about the number of people starting college every year (19.9 million students in 2019).

And the university can generate upwards of a quarter million dollars from one introductory course.

That number is … staggering.

So what now?

The not-so-hidden problem of higher education is that university courses are built on the backs of those who are highly educated but cannot find a permanent role. Why? Because the very universities they teach for eliminated job security by replacing tenured roles with highly precarious part-time positions. The tenure roles that are still available are highly competitive, often being filled by professors that already have a tenure track position at a different university. Therefore, few options outside of adjuncting exist for these professionals who want to stay in higher education.

This inappropriate (and what should be illegal) pay structure is one of the most glaring, disturbing, and leading failures of academia and higher education in general. The courses and education offered by universities are built from the materials, time, energy, and resources of adjuncts. Without them, there is no higher education. Adjuncts need as much as support as their tenure-track peers through fair compensation, financial packages to save for retirement, mentorship and personal growth, technical resources to advance teaching practices, and others. Without more concrete support, there is little incentive to stay in academia.

Based on the estimated values above (keeping in mind that these are estimates), universities can clearly afford to pay adjuncts a much higher salary while still achieving revenue goals to offer supplemental services to education. By leaning in to support adjuncts as much as they support tenure-track professors, institutes of higher learning can finally start the massive structural changes that will put their primary focus back on education. In doing so, future educators will have the tools and systems in place that allow them to focus on what truly matters: education.

Writing a Research Statement (with example)

Writing a Research Statement (with example)

Much like writing a teaching philosophy, a research statement takes time, energy, and a lot of self reflection. This statement is a summary of your research accomplishments, what you are currently working on, and the future direction of your research program. This is also the place to really highlight your potential contributions to your field. For researchers who are further along in their career, this statement may include information about funding applications that were reviewed, approved, as well as any applications that are going to be submitted within the next year.

When I’ve looked at research statements over the years, helping people prepare for the academic interview cycle, one thing I’ve noticed more than anything is that people tend focus solely on the tangible aspects of their research, essentially rehashing their CV or resume. Although their accomplishments are often great, it can result in a rather boring set of pages full of nitty-gritty details rather than an immersive story about research experiences and potential. If there is one thing you take away from this article, your research path is magical and you want your readers to be invested in your magical story.

Now, I realize in my particular area of research (statistics and numerical reasoning), magical is not the word that most people would use as a descriptor. But therein lies the catch. When you are applying for academic positions, you aren’t selling just your research focus. Rather, you are selling the idea of you, your work, and your potential. Yes, your focus is a part of this, but only one part. You are the truly magical component, and your research is just one aspect of that.

When I did my cycle through academic application season, I wanted the review board to see who I was as a researcher, but I also wanted them to see how I approached my research content. The value my research adds to the field is the icing on the cake. I know my research is valuable. Generally speaking, scientists agree that most research in always valuable. But I needed the review board to see more than just my research value because I was competing against literally hundreds of applications. In such a competitive arena, every component of my application portfolio needed to stand out and grab attention.

As with other aspects of your portfolio, your research statement has some core components:

- a brief summary of your research program

- an overarching research question that ties all the individual studies together

- what you are currently working on

- where your research program is expected to go

Talking through these core aspects in a serial, linear way can be rather … Boring. You definitely do not want to be placed in the discard pile simply because your portfolio wasn’t engaging enough. Which brings me to storytelling. When I say storytelling, I’m not saying academics need to be master weavers of fantasy, complete with plots and characters that draw people out of reality into an imaginary world. Instead, I mean that people need to be walked through a narrative that logically carries the reader from one sentence to the next. This research statements connects the readers to you and invests them in your future research potential. Every sentence should be designed to make them want to keep reading.

Don’t feel bad if this statement takes some time to draft. Not all of us are naturally gifted with the talent for wordsmithing. It, like many other aspects of your portfolio, takes time, effort, energy, and self-reflection. Each aspect should be built with thoughtfulness and insight, and those things cannot be drawn overnight. Take your time and really develop your ideas. Over time, you’ll find that your research statement will evolve into a mature, guiding light of where you’ve been and where you’re going. And your readers will enjoy placing your files in the accept pile.

Alaina Talboy, PhD Research Statement Example

“Science and everyday life cannot and should not be separated.” – Rosalind Franklin

Research Interests

Over the last eight years, my research interests have focused on how people understand and utilize information to make judgments and decisions. Of particular interest are the mechanisms which underlie general abilities to reason through complex information when uncertainty is involved. In these types of situations, the data needed to make a decision are often presented as complicated statistics which are notoriously difficult to understand. In my research, I employ a combination of quantitative and qualitative research methods and analyses to evaluate how people process statistical data, which has strong theoretical contributions for discerning how people may perceive and utilize statistics in reasoning and decision making. This research also has valuable practical implications as statistical reasoning is one of the foundational pillars required for scientific thinking. I plan to continue this research via several avenues in both theoretical and applied contexts.

Statistics and the Reference Class Problem

It is easy to feel overwhelmed when presented with statistics, especially when the meaning of the statistical data is not clear. For example, what does it mean when the newscaster says there is a 20% chance of showers? Does that mean it will only rain 20% of the day? Or that only 20% of the area will get rain? Or that 20% of the possible rain will actually fall? Without a knowing the appropriate reference class, or group from which the data are drawn, reasoners are often forced to make a decision based on an improper assessment of the numbers provided. (The correct answer is that out of 100 days with these weather conditions, rain occurs on 20 of them.) Although this is a rather benign version of the reference class problem, difficulties with this issue extends well into the very core of understanding statistics.

Statistical testing involves an inherently nested structure in which values are dependent on the expression of other values. Understanding these relationships are foundational for appropriate use and application of statistics in practice. However, difficulties understanding statistics has been widely documented throughout numerous fields, contributing to the current research crisis as well as patient diagnostic errors (e.g., Gelman & Loken, 2014; Ioannidis, 2005; Ioannidis, Munafò, Fusar-Poli, Nosek, & David, 2014; Pashler & Wagenmakers, 2012). Therefore, research that can improve general statistical literacy is highly sought after.

As a stepping stone toward the more difficulty reference classes in statistics, a slightly less complicated version of the reference class problem can be found in Bayesian reasoning tasks (e.g., Gigerenzer, Gaissmaier, Kurz-Milcke, Schwartz, & Woloshin, 2007; Gigerenzer & Hoffrage, 1995; Hoffrage, Krauss, Martignon, & Gigerenzer, 2015; Johnson & Tubau, 2015; Reyna & Brainerd, 2008; Sirota, Kostovičová, & Vallée-Tourangeau, 2015; Talboy & Schneider, 2017, 2018, in press). In these types of reasoning tasks, there are difficulties with representing the inherently nested structure of the problem in a way that clearly elucidates the correct reference class needed to determine the solution. Additionally, computational demands compound these representation difficulties, contributing to generally low levels of accuracy.

In my own research, we have tackled the representational difficulties of reasoning by fundamentally altering how information is presented and which reference classes are elucidated in the problem structure (Talboy & Schneider, 2017, 2018, in press). In a related line, we break down the computational difficulties into the component processes of identification, computation, and application of values from the problem to the solution (Talboy & Schneider, in progress). In doing so, we discovered a general bias in which reasoners tend to select values that are presented in the problem text as the answer even when computations are required (Talboy & Schneider, in press, in progress, 2018). Moving forward, I plan to apply the advances made in understanding how people work through the complicated nested structure of Bayesian reasoning tasks to the more difficult nested structure of statistical testing.

Reference Dependence in Reasoning

While completing earlier work on a brief tutorial designed to increased understanding of these Bayesian reasoning problems through both representation and computation training (Talboy & Schneider, 2017), I realized that the reasoning task could be structurally reformed to focus on the information needed to solve the problem rather than using the traditional format which focuses on conflicting information that only serves to confuse the reasoner. In doing so, we inadvertently found a mechanism for reference dependence in Bayesian reasoning that was not previously documented (Talboy & Schneider, 2018, in press).

Reference dependence is the tendency to start cognitive deliberations from a given or indicated point of reference, and is considered to be one of the most ubiquitous findings through judgment and decision making literature (e.g., Dinner, Johnson, Goldstein, & Liu, 2011; Hájek, 2007; Lopes & Oden, 1999; Tversky & Kahneman, 1991). Although the majority of research documenting reference dependence comes from the choice literature, the importance of context in shaping behavior has also been noted in several other domains, including logical reasoning (Johnson-Laird, 2010), problem solving (Kotovsky & Simon, 1990), extensional reasoning (Fox & Levav, 2004)—and now in Bayesian reasoning as well (Talboy & Schneider, 2018, in press).

I parlayed my previous research on representational and computational difficulties into the foundation for my dissertation, with an eye toward how reference dependence affects uninitiated reasoners’ abilities to overcome these obstacles (Talboy, dissertation). I also evaluated the general value selection bias to determine the circumstances in which uninitiated reasoners revert to selecting values from the problem rather than completing computations (Talboy & Schneider, in progress, in press). I plan to extend this line of research to further evaluate the extent to which a value selection bias is utilized in other types of reasoning tasks involving reference classes, such as relative versus absolute risk.

Advancing Health Literacy

Although the majority of my research focuses on the theoretical underpinnings of cognitive processes involved in reasoning about inherently nested problem structures, I also have an applied line of research that focuses on applying what we learn from research to everyday life. We recently published a paper geared toward the medical community that takes what we learned about Bayesian reasoning and applies it to understanding the outcomes of medical diagnostic testing, and how patients would use that information to make future medical decisions (Talboy & Schneider, 2018). I also led an interdisciplinary team on a collaborative project to evaluate how younger and older adults evaluate pharmaceutical pamphlet information to determine which treatment to use (Talboy, Aylward, Lende, & Guttmann, 2016; Talboy & Guttmann, in progress). I plan to continue researching how information presented in medical contexts can be more clearly elucidated to improve individual health literacy, as well as general health decision making and reasoning.